GSSP and Cebu Seed Savers Renew Commitment to Expand Organic Seed Production in Cebu Province

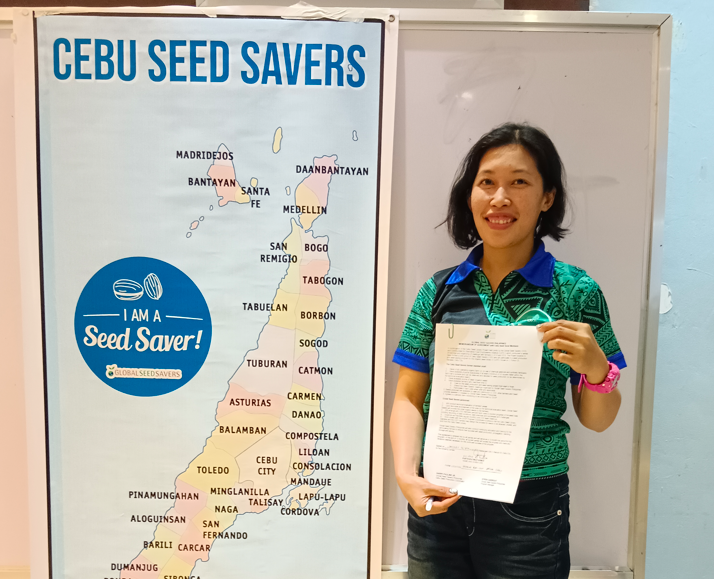

In January 2023, Global Seed Savers Philippines (GSSP, as represented by Harry Paulino, our Cebu Seed Production Coordinator) and our Cebu partner farmers gathered together to discuss the vital role of organic seed production within our communities. Farmers from all around Cebu Island came to this gathering. We had participant farmers from Argao, Sibonga, Car-Car, San Fernando, Naga, Aloguinsan, Catmon, San Remegio, Bogo, and Metro Cebu.

Of the many crucial discussions we had, the most important were that of farmers expressing their deep understanding of their essential roles in food sovereignty and reaffirming their commitment to this work through seed saving.

During this event, twenty-eight farmers signed the Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with GSSP and agreed to dedicate a portion of their lot (with a minimum of 20 sqm) specifically for seed production.

This MOA will ensure that our partner farmers will have sufficient sources of organically produced seeds that are locally adapted for their farm and communities. It will also support Global Seed Savers’ Community Seed Libraries which will enable other farmers in the region to have access to these high-quality, organic, open-pollinated seeds.

We are so grateful for our partner NGO, Communities for Alternative Food Ecosystems Initiatives (CAFEi) for joining us at this event as witnesses to this milestone for our Cebu Program. It is a first towards Food and Seed Sovereignty, and will surely be a catalyst for more collaboration between GSSP and other farming communities in Cebu Province.

This gathering has enabled us to appreciate how far our programs on Food and Seed Sovereignty has come. It has also allowed us to revisit the reason for our work, as well as a re-appreciation of the integral role that farmers play in these goals! Our farmer partners are the backbone of our communities – they are the stewards of our lands and seeds!